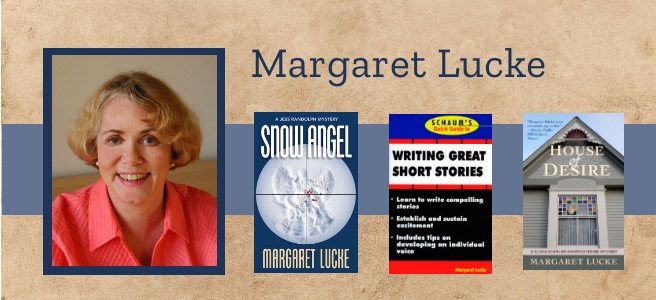

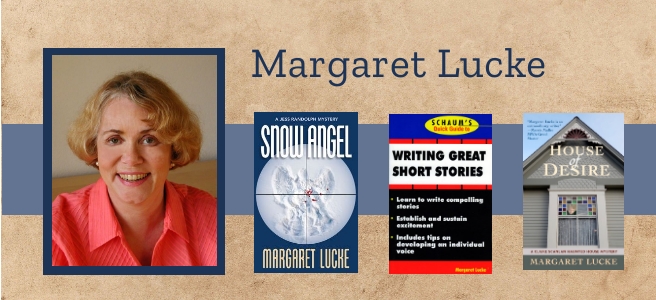

By Margaret Lucke

“The difference between reality and fiction? Fiction has to make sense.”

Variations of this quote have been attributed to numerous authors, from Mark Twain to Tom Clancy. All of them have had to deal with one of the big challenges of writing fiction—coming up with an ending that works.

How things end is one of the biggest ways in which fiction differs from reality. In a novel or a short story, the events of the tale are supposed to come to an orderly, or occasionally disorderly, resolution. The writer is supposed to tie the plot threads together, if not in a big bow then at least into a somewhat tidy knot. The ending doesn’t have to be a happy one, but it does have to make sense.

In real life endings are often messy. Whether it’s a romance, a marriage, a friendship, a job, a war, a civilization, the ending sometimes comes out of nowhere, a total surprise. Or it’s not so much an ending as simply a point where something stops or runs out of steam. Now and then we don’t even realize that an ending has occurred until much later.

But our human brains, aware that time marches steadily forward, like endings—and beginnings too. When we can bracket a set of events with a start point and an end point, that helps us impose a sort of logic on what’s going on in our lives and lets us achieve a measure of understanding.

Even better are the new beginnings that can follow an ending. This doesn’t happen so much with fiction unless the author is writing a series that chronicles the continuing adventures of a particular character. But in real life the closing of one door often provides us with a way to open another. New possibilities arise; we have new opportunities to reinvent ourselves.

That’s what drives our celebration of New Year’s Eve. The end of the year marks the start of a new one, a fresh page offering hope and the potential for better things to come. We make resolutions of a different kind than the ones we mean when we talk about the resolution of the plot in a work of fiction. We resolve to get organized, to lose weight, to become better people. We entertain the belief—though by now we realize that this may be another work of fiction—that the coming year will be better than the one that has just passed.

Right now we’re in that annual season of endings and beginnings. Last week, in celebration, we put on silly hats (well, not me, but some of us), we blew our noisemakers, we counted down as the ball on tower at Times Square descended, we lifted glasses of champagne in a toast (you could count me in for that one).

We said farewell to 2025, and some of us may not be sorry to see it go. We are ten days into a fresh new year, 2026, which at this point is full of hopes and dreams and positive potentials. May all they all turn out not to be fiction but become a positive reality.

I’ll close with my favorite New Year’s toast, my wish for all of you:

“May 2026 be better than any year that’s come before, and worse than every year that will follow it.”

Cheers, everyone! And Happy New Year!

You must be logged in to post a comment.