Bop City Swing, or When Writers Click

By M.E. Proctor

We should write something together, I’ve heard these words many times. The suggestion is always vague and about as binding as the clichéd ‘let’s do lunch one of these days’. Many years ago, a friend and I planned to write a book. He was a big science fiction fan, so that’s what we decided to do. I delivered the first chapter. My friend never produced chapter 2, and I ended up doing the entire thing. It turned into a four-book dystopian series, The Savage Crown.

So, when fellow crime writer Russell Thayer typed in a social media chat that “Tom should go after Gunselle someday. Imagine the interrogation scene!” I agreed that bringing our two recurrent short story characters together was a cool idea, but I doubted it would go anywhere.

I was wrong. We’re a year later and Bop City Swing is on the bookshelves. Even better, Russell and I are working on another mystery featuring the same two leads.

Russ’s creation is Vivian Davis, aka Gunselle, a contract killer. He has written more than twenty short stories spanning the late 1930s-early 1950s with her in the starring role. My guy (he’s in a dozen stories so far) is Tom Keegan, a homicide detective in 1950 San Francisco. A professional killer and a cop, in the same place at the same time … sounds like a match made in Noir heaven.

Early last year, Russ and I both happened to have pieces published at the same time in two different magazines. A mash-up—in the vein of CSI meets Law & Order—was top of mind again and we started brainstorming ideas for a short story. What if she’s hired to bump him off … What if they’re after the same killer… We eventually decided to build the story around a political assassination that would involve both characters, coming at it from their respective angles. The detective investigates the case, in straight procedural fashion, and the contract killer is embroiled in it sideways. She didn’t commit the crime.

We never discussed the mechanics of the collaboration. It felt natural to tell the story from a double point of view (POV), Russ writing the Vivian-Gunselle chapters, while I wrote Tom’s scenes. The differences in our styles fit the particular voice of our respective characters. If there were awkward disparities or rough edges, we figured we could polish them off after the first draft.

Russ sent me a snippet of Gunselle being hired for a job she dislikes—fixing somebody else’s mess, i.e. the assassination (that plot line was discarded later on)—and a few days later, I sent him Tom’s arrival at the crime scene, the ballroom of a luxury hotel. The suspect is a musician in the jazz band hired for the event.

Everybody knows that most of the research should be done before starting to write the story, it’s a lot more efficient, but we were both eager to get something going. Now, with two scenes drafted, we had to make sure we were historically correct on the when and the where.

The when would be 1951, an election year. That November, San Francisco re-elected the incumbent republican mayor, Elmer Robinson. The fictional who (the victim) would be Charles Forrester, the democratic challenger launching his campaign at a June fundraiser. Where would be the Palace Hotel, conveniently located downtown, with a good size ballroom—an internet deep dive delivered period-accurate floorplans.

We knew when, where, and who, but like our two lead actors, we were stumped by the motive. Why was Charles Forrester shot? We wouldn’t find out for a while.

Writing a story is like a treasure hunt. Every sentence, written on the fly, contains potential clues. Here’s an example. The decision to make the killer a jazz trumpeter gave the plot a definite slant. It also gave us the opportunity to dig into the rich Bay Area music scene of the early 50s, the various clubs, the talent on display, the racial tensions, the lure of the city at night, the early involvement of the Mob in the drug trade. Russ had touched on the music angle in some of his stories and brought all that background into the plot, with great secondary characters. One of them, Maggie, became central to nailing down the motive and the final resolution. Through Maggie, we also touched on the war, only six years in the past, and its aftermath, how deeply it scarred many characters in the story.

Very soon, the project was no longer a short story. Bop City Swing had turned into a book.

During the months it took to complete a solid first draft, we had a couple of mini-debates. One of them was about who would enter the scene first.

Homicide cops always get there after the fact, by definition. We decided to start with Gunselle and put her in the ballroom, at the very beginning, before the shots ring out. That gave us the story hook. She was hired for the hit and somebody beat her to it. She’s pocketed the down payment. For doing nothing. As a professional, it sticks in her craw.

Another discussion was about the key confrontation between our two characters. Up to that climactic moment, they’d both gone through their moves separately, with only a glancing accidental contact that showed mutual interest. Yes, this is where it gets sexy … Who would write that scene, in whose POV? We considered writing it twice, in a ‘he says, she says’ tango, but it proved clunky. I wrote the initial scene, from Tom’s voice, then Russ took it and turned it around. It worked a lot better that way, Gunselle initiates the event and is the more active character. It was also fun to write Tom’s reaction afterwards.

We initially wrote our respective scenes separately. After a few weeks, we built a master document that we carried all through to the end, highlighting changes, constantly adjusting things. Russ writes snappy action scenes and I tend to be atmospheric. In the master document, we started blending things. He added bite and I added background.

Mid-way through the process, we built a timeline. The characters were all in motion and the investigation picked up speed. A beat-by-beat sequence of events helped us figure out the ending. None of what happens in the last act was in the cards from the start.

The time we took to consider options, writing them and discarding parts of them, might appear to be a waste but was crucial in coming up with the best solution. The beginning of the story, in particular, was rewritten multiple times. Part of the fun in a collaboration is having your partner put something on the table that you would never have come up with on your own.

Writing is a solitary pursuit. Sometimes, it feels good to share. Russ and I had so much fun, we’re doing it again. There will be more Tom and Gunselle in the future. I’ll keep you posted!

—-

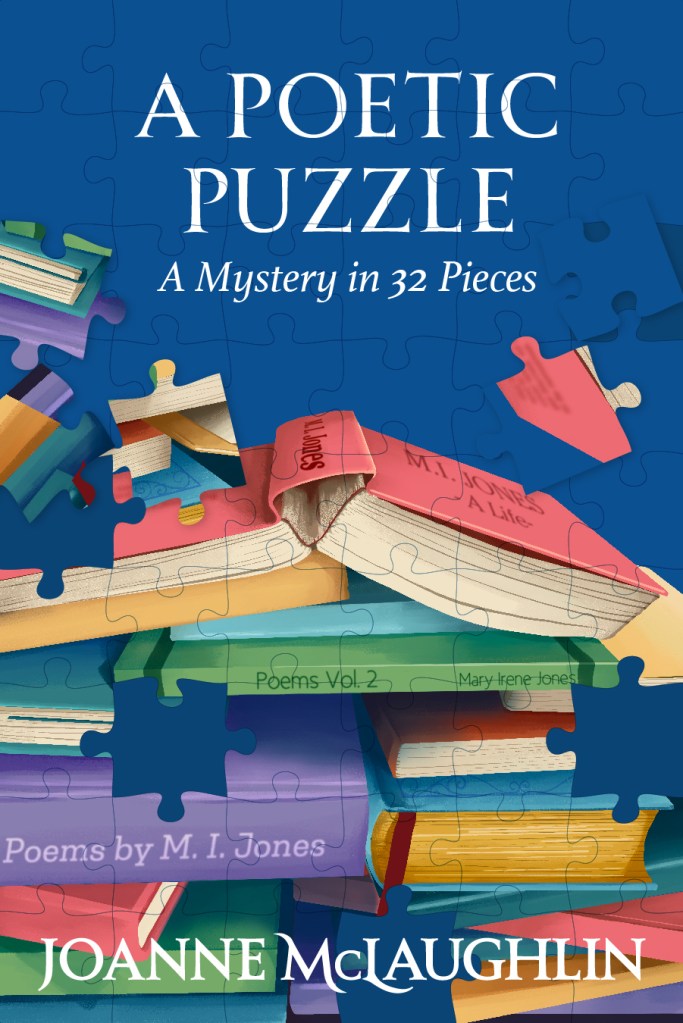

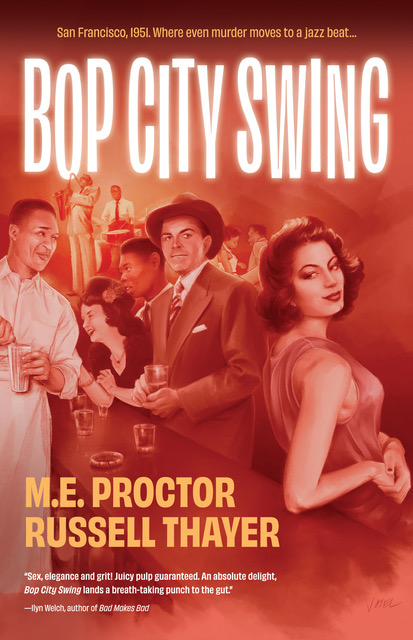

Bop City Swing

San Francisco. 1951.

Jazz is alive. On radios and turntables. In the electrifying Fillmore clubs, where hepcats bring their bebop brilliance to attentive audiences. In the posh downtown venues where big bands swing in the marble ballrooms of luxury hotels.

That’s where the story begins, with the assassination of a campaigning politician during a fundraiser.

Homicide detective, Tom Keegan, is first on the scene. He’s eager, impatient, hot on the heels of the gunman. Gunselle, killer for hire, is no longer there. She flew the coop, swept away in the rush of panicked guests.

They both want to crack the case. Tom, because he’s never seen a puzzle he didn’t want to solve, no matter what the rules say. Gunselle, because she was hired to take out the candidate and somebody beat her to it. It was a big paycheck. It hurts. In her professional pride and wallet.

The war has been over for six years, but the suffering and death, at home and abroad, linger as a horror behind the eyes of some men. And one young woman.

Bop City Swing is the brainchild of Russell Thayer, author of the Gunselle stories, and M.E. Proctor, who occasionally takes a break from Declan Shaw, her Houston PI, to don Tom Keegan’s gray fedora.

Buy Links:

Bop City Swing is available in eBook and paperback

On Amazon at https://www.amazon.com/Bop-City-Swing-Proctor-Thayer/dp/B0F4DSSQ9V/

From reviews:

“A wild ride down the neon-lit streets of post-WWII America, with bebop wailing in the nightclub on the corner, the white witch pumping through the veins of the junkie on the barstool, three slugs draining the life from the charismatic politician with a shady past, and enough snappy dialogue to light up the faces of Raymond Chandler and James M. Cain.”

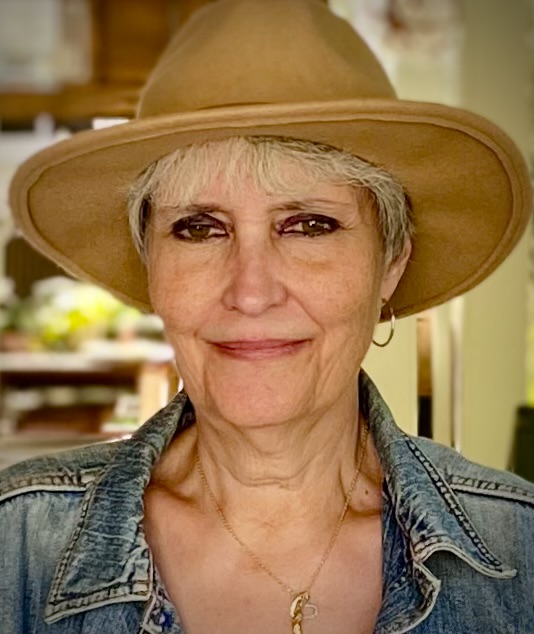

M.E. Proctor (www.shawmystery.com) was born in Brussels and lives in Texas. The first book in her Declan Shaw PI series, Love You Till Tuesday (2024), came out from Shotgun Honey, with the follow up, Catch Me on a Blue Day, scheduled for 2025. She’s the author of a short story collection, Family and Other Ailments, and the co-author of a retro-noir novella, Bop City Swing. Her fiction has appeared in Vautrin, Tough, Rock and a Hard Place, Bristol Noir, Mystery Tribune, Shotgun Honey, Reckon Review, and Black Cat Weekly among others. She’s a Derringer nominee.

Social Links

Author Website: www.shawmystery.com

On Substack: https://meproctor.substack.com

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/martine.proctor

Twitter: https://twitter.com/MEProctor3

BlueSky: https://bsky.app/profile/meproctor.bsky.social

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/proctormartine/

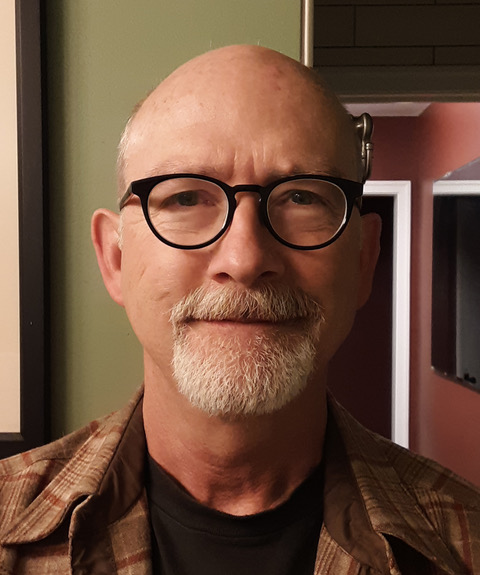

Russell Thayer’s work has appeared in Brushfire, Tough, Roi Fainéant Press, Guilty Crime Story Magazine, Mystery Tribune, Close to the Bone, Bristol Noir, Apocalypse Confidential, Cowboy Jamboree Press, Hawaii Pacific Review, Shotgun Honey, A Thin Slice of Anxiety, Rock and a Hard Place Press, Revolution John, Punk Noir Magazine, Expat Press, Pulp Modern, The Yard Crime Blog, and Outcast Press. He received his BA in English from the University of Washington, worked for decades at large printing companies, and currently lives in Missoula, Montana. You can find him lurking on Twitter @RussellThayer10.

You must be logged in to post a comment.