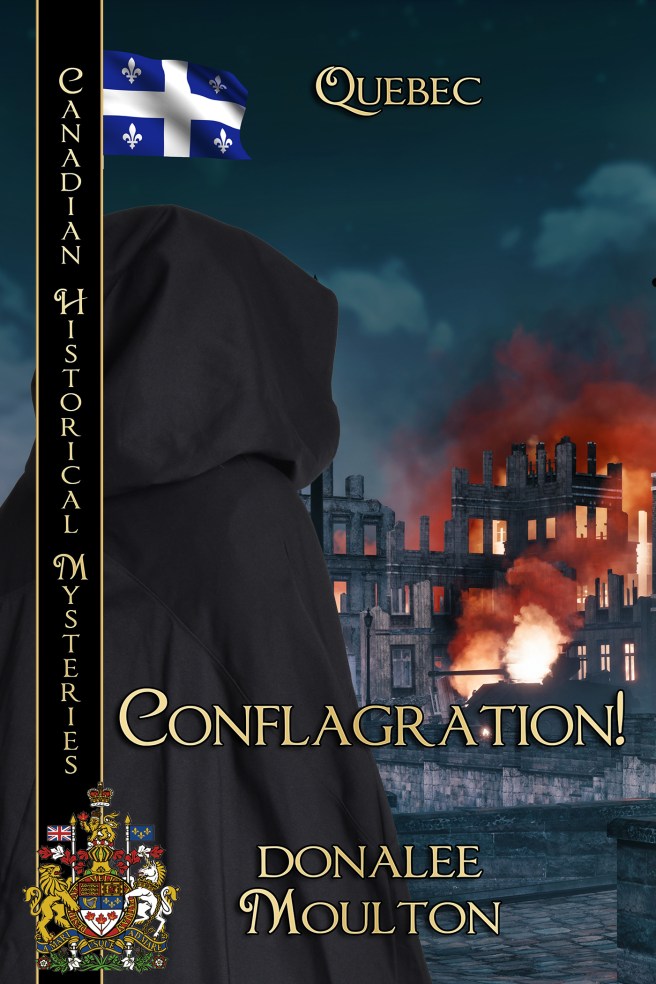

This past holiday there was a special present under the tree – my new novel Conflagration! This is the seventh book in BWL Publishing’s Canadian Historical Mysteries series, and it takes us back almost three centuries to New France and an era when slavery was surprisingly and sadly commonplace. I’d like to share the opening pages with you.

CHAPTER 1

Montréal

Friday, April 9, 1734

Mud is everywhere. It defines Montréal in April. The snow continues its laborious melt, the ice in the St. Lawrence jostles the shoreline, the clouds hover relentlessly close to earth, and everywhere there is heavy, wet, sticky muck. It adheres to the sides of shoes, the bottoms of coats, and the brims of hats whipped to the ground by winds, there one minute, gone the next.

I look down. My boots are caked in grime, a primordial ooze from the earth, from under the sea, from crevices unknown. I will spend much of this evening cleaning heels, toe caps, and outsoles only to have more mud adhere tomorrow. These caked brown scars are visible reminders that I am not at home. Not at home in this town. Here I have no roots, no history.

Home is Acadie, another world away in another part of New France. My home, admittedly, has mud, but it is the mud pigs roll in to cool their skin, the mud farmers use to build dykes, the mud kids make patties with under the spring sun. Montréal mud is a nuisance, a bother, a reminder of life’s inconveniences.

I am feeling sorry for myself. I am missing my family. It happens. I accept the ache, acknowledge its origins, and move forward, literally through more mud. I remind myself of Madeleine, my wife. She makes life in here bearable. She makes life breathable.

The afternoon sun hides behind clouds. But even in disguise, its demise for the day is evident. Soon it will be dark. I need to push onward, deliver these papers, and make my way home before nightfall. Before the mud becomes invisible, and treacherous. The ground is still hard and much of it frozen; mud will not break a fall, but it will cause one. I need to be careful. For Madeleine.

* * *

François de Béréy’s home is large by Montréal standards. Indeed, it is large by any standard. It rises three floors in the heart of the merchants’ quarter on rue Saint-Paul where it announces its presence to fur traders and aspiring businessmen without saying a word. It sits across from the Hôtel-Dieu de Montréal, the town’s convent and hospital. Three sisters in full habit are outside getting, I assume, a much-needed break from the rigors of tending to the ill and the injured. Immediately, I feel guilty for my selfishness, for a little mud. I nod at the three nuns acknowledging their presence and, I hope, their worth. The three women nod back.

I turn away and knock on the door in front of me. A young servant girl answers. She is about seventeen, dark brown hair pulled back in a bun, pleasantly overplump. She wears a white apron. Her head is bowed. “Philippe Archambeau pour Monsieur de Béréy, s’il vous plait.”

The young woman scurries off. She is back in a few seconds. She ushers me into the foyer. She does not look at me.

My business is over as quickly as it began. Documents delivered, and my day is done. The sun is struggling with the horizon, and losing. I would like to be home before it cedes the daily battle. I hurry down to the street. Two women are talking at the bottom of the steps, a servant and a Panis slave. They turn their backs to me and continue their conversation. As I walk past, I hear only one word: conflagration.

The Panis woman, likely, I thought, from a tribe south of Montréal, turns in my direction as I pass. It is a vacant look; I doubt she even sees me. But I see her. In two days, I will put a name to her face: Marie-Manon.

* * *

A heavenly aroma greets me as a walk through the front door. We live several streets away from the merchants’ quarter, on rue Saint-Antoine, closer to where I work as a court clerk. Madeleine knows somehow today was a long day and a hot beverage will be welcome. The tea, a Bohea blend infused with orange peel, is a special treat. It helps to warm my chilled bones and reassure my feet they will work tomorrow. Madeleine places my boots at the front door. I will tackle them later. Supper is hot and satisfying, smoked ham with potatoes, cabbage, and onion. More tea follows the meal. As does conversation. This is our time. Madeleine listens with her ears and her heart. This is my favorite time of day.

And I talk about mud. My wife knows I am not really talking about mud but about Montréal, this town that is my home and not my home. “There is mud in Acadie,” she says gently. She pats her stomach, almost absently, and reminds me that soon this town will also be the home of our first child.

“I’m sorry.” It’s the least I can say. What I can do is make our conversation what it should be and what it usually is: meaningful.

“I was in the lower town today.”

Madeleine smiles. “I bet it was muddy.”

“I saw a Panis slave. My guess, she is from the Fox Nation. Sold to someone here.”

“You see slaves every day. Yet you remember this one.”

“You are, as usual, right. I saw several slaves today on rue Saint-Paul alone. And a young servant girl. It all disconcerts me still.”

I am familiar with slaves. We have slaves in Acadie, but they work the farms, the field, the land as we all do. They seem part of the landscape. Perhaps they do not feel that way. I say this out loud to Madeleine. She does not dismiss the notion as odd as it may be in this town of 3,000 people that includes hundreds of slaves, maybe more.

“Do these slaves look differently to you? Do they act differently?”

They do not, and they do. “It is the vacant stares, the abbreviated eye contact. It does not sit well in my heart.”

“Another cup of tea will solve that.”

I will come to realize that what I see is the look of those imprisoned. It is the face of those who have no means of escape. Later I will associate it with the wall that surrounds Montréal.

I hate that wall. It closes me in. It is supposed to make me feel safe. It doesn’t.

* * *

Madeleine is sleeping. She sleeps a lot these days. I understand her body needs this even though she fights it. My mother also slept when she was with child, my brothers and sisters.

I take the last of the tea, reheated on the hearth. Madeleine would not approve. She would make a fresh pot, and we would talk. Tonight, she sleeps, and I look at the stars. They are the same stars I see in Acadie. And they are not.

From my front door, from most front doors, the wall is not visible. It is as if it does not exist. But we all know it surrounds us. Or almost surrounds us. For nearly twenty years, Gaspard-Joseph Chaussegros de Léry has planned, managed, and propelled the building of ramparts literally designed to protect Montréal from its enemies, primarily the British. New France’s chief engineer will see this wall finished, this town cocooned in stone.

The wall is flanked. Anyone who dares attack Montréal will know what faces them before they ever arrive at these ramparts. That is deliberate, and doable in large part because the town lies on moderately flat land. Curtain walls and strongholds and drawbridges and posterns span 3,500 metres. We are fortified in black limestone and grey crystalline.

The wall speaks to the power of France, and to the consideration of our King, Louis XV, and his famous great grandfather before him. It exudes authority.

It also promotes the trades. Montréal is flourishing inside these ramparts. The wall requires stone fitters and masons. Sawyers and blacksmiths and haulers are also needed. There is enterprise in the rise of these enclosures.

The wall speaks as well to those who seek to make money. It says, “You are safe here. Your business will thrive.”

With the wall comes commerce, particularly fur trading. Businesses spring up around this endeavour. Indeed, Montréal is a trading post. Where there is trade, there is community and the shops, markets, and supports needed to bolster and enshrine a town. In the time since the wooden palisade that once circled Montréal was replaced with this new wall, approximately 400 houses have been constructed. And the wall is not yet finished.

Of course, prosperity requires judicial overwatch. Our courthouse bustles with the legal business of business. It also punishes, as it must, those who dare to defy the King’s laws. I know this firsthand. I sit each day in that courthouse. I record the testimony of those who walk through its doors. Many faces are familiar. Many are unknown.

None will leave as great an impression as the twenty-five who will walk through its doors in the next twenty-two days.

Life is good. It is filled with family, friends, and furry critters. There is yoga four times a week; I wish it could be more. That is, I know, a wish I could fulfill.

Life is good. It is filled with family, friends, and furry critters. There is yoga four times a week; I wish it could be more. That is, I know, a wish I could fulfill.  That’s an interesting question. As a freelance journalist, I wrote on everything from intellectual property to the armoured truck industry to eel grass. Accuracy was paramount as was engagement. However, the most difficult piece I ever wrote was for “Lives Lived” in The Globe and Mail. It was a tribute to my mother following her death in 2020. It was so difficult to write because it was so personal. I had no perspective, and I feared I would not “get it right.” The only thing I know for sure: Mama, would have told me not to worry. And there would have been a hug.

That’s an interesting question. As a freelance journalist, I wrote on everything from intellectual property to the armoured truck industry to eel grass. Accuracy was paramount as was engagement. However, the most difficult piece I ever wrote was for “Lives Lived” in The Globe and Mail. It was a tribute to my mother following her death in 2020. It was so difficult to write because it was so personal. I had no perspective, and I feared I would not “get it right.” The only thing I know for sure: Mama, would have told me not to worry. And there would have been a hug. My mother taught me to love language – and to respect it. She cared about words and getting the words right. She was my greatest influence.

My mother taught me to love language – and to respect it. She cared about words and getting the words right. She was my greatest influence.

You must be logged in to post a comment.