Character Matters

by Tilia Klebenov Jacobs

The prep stage of writing can be a time of enchantment when characters and motivations emerge like flowers blooming. As I laid the groundwork for a story that would eventually be called “Perfect Strangers,” I felt as though I were not creating so much as discovering the answers to key questions. Specifically, what kind of person creates multiple identities in order to rob a marijuana dispensary?

Authors say there are two kinds of writers, plotters and pantsers. Plotters write outlines, sketch character bios, run their stories past lawyer friends to see exactly what kind of trouble they’ve gotten their protagonist into, and generally research down to the last stray molecule of information. By contrast, pantsers prefer to fly by the seat of their…trousers.

I am a plotter. This may have something to do with my days as a middle school teacher, when I would routinely tell my students that failing to prepare is preparing to fail. Mostly, though, it just has to do with being me. I like knowing where I’m going before I set off, and I like knowing who I’m writing about before we embark on mayhem together.

For “Perfect Strangers,” I filled in a bio sheet that I’ve developed over the years. I started with the basics: name, age, sex/gender identity, job; and went on to such details as education, hobbies, and living and work spaces. I decided how many kids were in the family of origin, whether the parents were married, and if so whether it was a happy marriage. I described my character’s religion, ethics, and politics, and added a brief timeline of his life up till now. Thus did I make my protagonist, Gershom McKnight, a recently paroled convict. He was born in Providence, Rhode Island, the single child of unhappy parents who did not encourage their son’s talent in visual arts (useful for a career as a forger later in life). He was a juvenile delinquent who became a felon at age eighteen, and his best friend is his cellmate.

My biographical information on Gersom also told me how he sounded. My notes under “Tone and Narrator” read as follows:

Narrator has spent 10ish years in prison. S/he, but probably he, is smart, resilient, and resourceful, but at best an autodidact. Can have plenty of humor, but not lotsa highfalutin’ vocab and descriptions. Tone is conversational, a cross between boasting and confiding. He knows stuff, and how to do stuff, and is proud of it.

Suddenly, I could hear my fictional character talking. I knew his voice, his sense of humor, his wry asides. Now he and I could tell his story.

Many of the details I come up with never appear in the story they undergird. For example, Gershom’s family life is never mentioned in “Perfect Strangers.” However, all these data points serve me in the aggregate by giving me a precise picture of who I’m dealing with, what they sound like, and how they will behave once the action starts. For me, it is a joyful process of discovery.

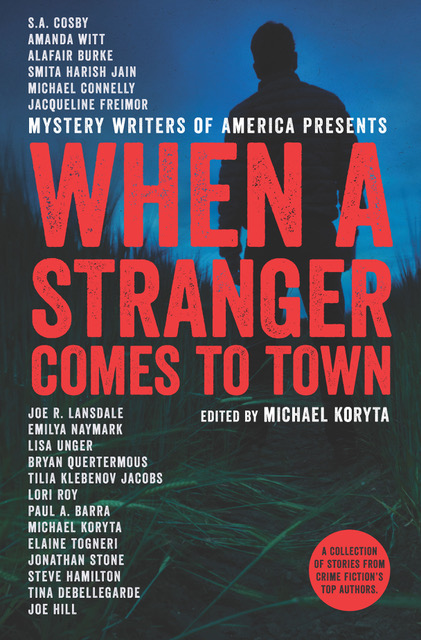

Mystery Writers of America Anthology

“It’s been said that all great literature boils down to one of two stories — a man takes a journey, or a stranger comes to town. While mystery writers have been successfully using both approaches for generations, there’s something undeniably alluring in the nature of a stranger: the uninvited guest, the unacquainted neighbor, the fish out of water. No matter how or where they appear, strangers are walking mysteries, complete unknowns in once-familiar territories who disrupt our lives with unease and wonder. In the newest collection of stories by the Mystery Writers of America, each author weaves a fresh tale surrounding the eerie feeling that comes when a stranger enters our midst, featuring stories by prolific mystery writers such as Michael Connelly, Lisa Unger, and Joe Hill.”

IndieBound / Bookshop.org / Barnes & Noble / Amazon / Books-A-Million / Audible.com

Tilia Klebenov Jacobs is the bestselling author of two crime novels, one middle-grade fantasy book, and numerous short stories. She is a judge in San Francisco’s Soul-Making Keats Literary Competition, and a board member of Mystery Writers of America-New England. HarperCollins describes her as one of “crime fiction’s top authors.” Tilia has taught middle school, high school, and college; she also teaches writing classes for prison inmates. She lives near Boston with her husband, two children, and pleasantly neurotic poodle.

Website: http://www.tiliaklebenovjacobs.com/

FB Author Page: https://www.facebook.com/Authortiliakj

Twitter Handle: @TiliaKJacobs

You must be logged in to post a comment.