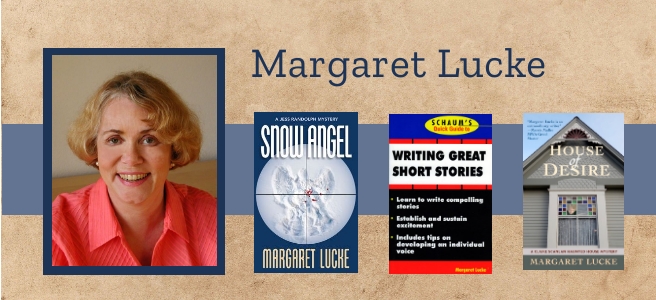

By Margaret Lucke

“Many people hear voices when there’s nobody there.

Some of them are called mad and are shut up in rooms where they stare at the walls all day.

Some of them are called writers and they do pretty much the same thing.”

– Mystery Author Meg Chittenden

Do you hear voices when there’s no one there? Or have invisible people accompany you as you go about your daily activities?

Yes? Then welcome to the club. A fairly exclusive club, as it turns out.

A few years ago I took a short road trip with my good friend Penny, whom I’ve known since our college days. As we drove we chatted, the way old friends do, about our dreams, our daily lives, and the ways we would fix the world if only someone had the good sense to put us in charge. I mentioned the book I was writing, and she asked me this:

“What’s it like to have people running around inside your head all the time?”

The question startled me. “What? You mean you don’t have them?”

“Not at all. I can’t imagine it. Is it like hearing voices?”

Now, Penny is someone with a direct line to the creative process. She’s a brilliant cook who serves the most amazing dishes. A talented seamstress who tossed together fantastic costumes out of nothing for our college theater. A devoted lover of art, music and literature. Yet she didn’t have people occupying her head? How did her brain work then? How could she possibly think?

Since then, I’ve discovered that it’s actually rare to have a head filled with people. I’ve met other fiction writers who share this trait, but usually when I mention it to someone I get a strange look, as if the person is assessing whether I need to the services of my friendly neighborhood mental institution.

Perhaps I do. But I have a hard time understanding how anyone’s mental processes could possibly function in a different way.

I’ve had people wandering around in my brain ever since I can remember. They’re my equivalent of imaginary playmates. They tell me stories, ask me questions, give me answers, and help me clarify my thinking. They keep me company when I take long walks and as I’m trying to fall asleep at night. I’ve heard that writing is a lonely profession, and in lots of ways that’s true. But even when I’m at my desk by myself, I’m never really alone.

Some of the people in my head turn into characters in my novels and short stories. Often what sparks a story is a snatch of conversation that comes drifting through my brain. That sets me on a journey to discover who’s talking, and how they’re connected to each other, and what they’re discussing and why. Gradually the story emerges.

My first novel, A Relative Stranger, began this way. Walking to a bus stop, my mind let me overhear a late-night phone conversation. The woman who answered the phone clearly found the call unwelcome. The man who had called sounded desperate to connect with her. When I reached my destination, I wrote the conversation down. Who were these people?

The woman turned out to be a private investigator named Jess Randolph; the caller was her estranged father, turning up after many years to ask for her help because he was the prime suspect in a murder. Was he guilty? Would she help him? What would they do next?

In my story “Haircut,” a flash fiction tale that was recently published by Guilty Crime Fiction Magazine (you can read it here), I woke up one morning listening to the voice of a young woman named Hallie as she described the abrupt ending to what she had hoped would be an enduring romance. I got out of bed, stumbled to my computer, and wrote down what she had to say.

I may be making the process sound easier than it is. The people in my head don’t always want to be promoted from random guest to Story Character. Once they have me intrigued, they all too often ignore me. They fight me off or hide behind the curtains. They take a vow of silence. Sometimes they disappear.

And sometimes, gradually, after I beg and plead and cajole, they start to reveal their secrets.

At last the story is underway.

You must be logged in to post a comment.