Beginnings and endings are the hardest part of writing for me. (That’s today. On other days it’s the muddled middle.) Some writers have arresting, captivating openings that grab the reader and carry her along into a ninety-thousand-word novel. I’m not one of those, but I can eventually get a few words on the page to get the story moving. For me the greater challenge is endings.

Some years ago I listened to Andre Dubus III talk about his new book, House of Sand and Fog, which led him to talk about how he’d grown as a writer. He didn’t like his first book, Bluesman, because he considered it sentimental. His disdain for this failure in craft was obvious, and when I met him at a writers’ event years later, the subject came up again. As I listened to him touch on the challenges in his work, I understood that for him an ending that is sentimental is also in some ways dishonest, an inability to reach deeper for something that was true. I had just purchased TheGarden of Last Days, and read it with that in mind. There is nothing sentimental in that book, least of all in the ending.

Several critics have explored the link between the traditional and cozy mystery and comedy; noir crime fiction has been linked to tragedy. At the end of the cozy mystery, the world is set right again; the villain has been identified and brought to justice of some sort; the lesser crimes of other characters are brought to light and justice is visited on them in various ways, perhaps public censure or shame or remorse; and the minor romance barely acknowledged sometimes comes to light and there is a new beginning for a young couple. All is right with the world. From Restoration Comedy to Agatha Christie and writers today, it is hard for a reader of cozies or traditional mysteries to be satisfied with less. An unrequited love or an unchallenged con artist will annoy some readers as much as a dangling participle will menace the peace of mind of a copy editor. And I understand this. There is something deeply satisfying about the comedic ending, a moment that reassures us that the world aslant can be righted, that our inchoate ideals can be realized.

So how does a writer of traditional crime fiction compose an ending that is both true to the story being told and unsentimental? Sometimes I think this question is just one more obstacle to writing a satisfactory ending, and all I’m doing is complicating matters, making life harder for myself. I’m not unsatisfied with the ending of Family Album, the third in the Mellingham series, but I acknowledge that it is a tad sentimental (maybe more than a tad). But readers loved it because it fulfilled one of the hints at the beginning of the story, and a promise fulfilled, particularly about a possible romance, always brings a frisson of delight. But it was sentimental. At least it wasn’t mawkish.

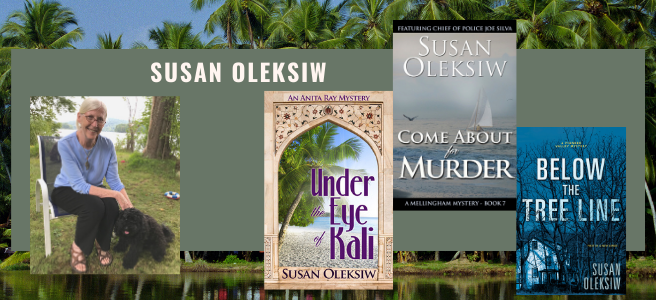

I don’t remember most of the endings in my books and stories but some stand out, for me at least. The ending of When Krishna Calls in the Anita Ray series required research, rethinking, and stepping back. A woman sentenced to prison looks out on her new world, listening to another prisoner, and is satisfied with the choices she has made. She won’t forget why she is where she is, and she won’t regret it. The ending of Friends and Enemies in the Mellingham series required several versions before I finally landed on the one that worked and fit with the rest of the story. An editor who read the ms and considered acquiring it mentioned how much she liked it (but not enough to take the book). Another ending that satisfied me is that in “Coda for a Love Affair,” in Devil’s Snare: Best New England Crime Stories 2024. The ending is simple, clear as cut glass and sharp.

Endings are hard because the easy ones come fast, are easy to write, and sit well on the page. And that’s the problem. They tempt us to take them, give a sigh of relief, and pat ourselves on the back for coming up with (rather than running carelessly into what looks like) the perfect line or paragraph to close out three hundred pages. Depending on how tired we are of the story and working on it, that ending will appear reasonable, acceptable, or a gift from the writing gods. So this is where I step back and wonder what Andre might think. I don’t have to get far into that mental exercise to admit that the first or even the thirtieth ending is not what I want.

If nothing else, writing keeps us humble. In our heads we hear perfect dialogue, snatches of prose so brilliant we’ll never need the sun again, but on the page, our pen does not cooperate (or the computer keyboard), and we end up with the mundane, the ordinary, the usual. I keep working on endings but I know I fall short most of the time. As do we all. It’s encouraging to know that greater writers have the same struggles, the same challenges, the same doubts. With one eye on writers whom I admire, I keep at my own work, striving to meet my standards even if that means sometimes disappointing some readers. If I want better endings, I just have to keep at it until I get there.

Agatha Christie is regarded as the most popular mystery writer of all times. Since the publication of her first book in 1920, more than one billion copies of her books have been sold worldwide. She wrote her first detective story while working in a dispensary during the First World War. Her sister, Madge, bet Christie that she could not write a mystery in which she gave her readers all the clues to the crime and stump them at the same time. Christie proved Madge wrong, and The Mysterious Affair at Styles was published. Her second book sold twice as many copies as her first, and she found that writing flowed easily for her. In 1926, The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, gained her world acclaim. It is one of the most talked about detective stories ever written. Using a technique that had not been used before, many of her colleagues and readers accused her of breaking the mystery-writing rules. In her defense, she stated that rules are made to be broken and if done well, prove effective. Almost ninety years later, the controversy still remains. She’s gone on record to say that this Hercule Poirot mystery was her masterpiece.

Agatha Christie is regarded as the most popular mystery writer of all times. Since the publication of her first book in 1920, more than one billion copies of her books have been sold worldwide. She wrote her first detective story while working in a dispensary during the First World War. Her sister, Madge, bet Christie that she could not write a mystery in which she gave her readers all the clues to the crime and stump them at the same time. Christie proved Madge wrong, and The Mysterious Affair at Styles was published. Her second book sold twice as many copies as her first, and she found that writing flowed easily for her. In 1926, The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, gained her world acclaim. It is one of the most talked about detective stories ever written. Using a technique that had not been used before, many of her colleagues and readers accused her of breaking the mystery-writing rules. In her defense, she stated that rules are made to be broken and if done well, prove effective. Almost ninety years later, the controversy still remains. She’s gone on record to say that this Hercule Poirot mystery was her masterpiece.

You must be logged in to post a comment.