The Perils of Creating a Teen Amateur Sleuth

I am the author of seven published humorous cozy mysteries. While my adult female protagonist in The Holly Swimsuit Mystery Series is younger than I, the age difference between us did not present any verisimilitude issues when I created her personality, lifestyle, or career. One key element that made it easy was that she was based on me.

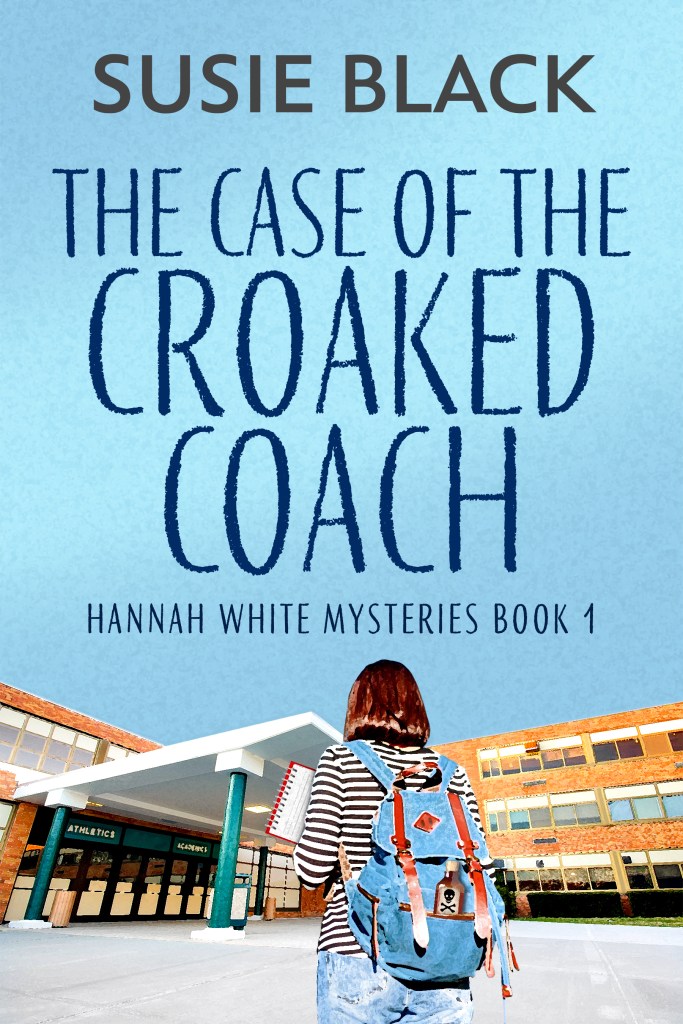

But writing a series with a teen amateur sleuth who was again based on me, this time as a high school newspaper investigative reporter, presented several challenges that had to be overcome to make the tale realistic. The Case of the Croaked Coach, the debut title of The Hannah White Mystery Series, was simultaneously the easiest and most difficult manuscript to write.

How much danger could I/should I put my young sleuth into?

Would she tell her parents what she was doing or lie to them?

Who would take a teenage amateur sleuth seriously? If she interrogated an adult suspect, would they even give her the time of day, much less answer her questions? How would she know what questions to ask?

If she had suspects in mind, how would she go about investigating them? How would she know what to do? How would she gain access to conduct her investigations?

If she did somehow discover proof that a suspect was the killer, would the homicide detective take her information and look into it, or blow her off?

The scene where the protagonist discovered her classmate holding the bloody murder weapon over the victim was harder to write than any other. While the series is based on my experience as a high school newspaper investigative reporter, I thankfully had never made such a gruesome discovery as Hannah White did. How should she react? Terrified? Shocked? Faint?

So, how did I overcome seemingly insurmountable challenges?

- I created two adult characters who interacted with the teenage sleuth:

Bart White: Hannah White’s uncle and the defense attorney for the teenage murder suspect.

H.S. Whiperski: A Private Investigator, Bart hired. H.S. tailored Hannah’s questions & the steps the teenage sleuth could realistically and safely take.

- I incorporated Hannah’s investigative reporter skills into how she approached suspects and the methods she employed to question them. Hannah questioned several teacher/ suspects under the guise of interviewing them for a story she was writing for the school newspaper.

- I created a group of Hannah’s friends called the Young Yentas. This group served as a sounding board for Hannah to bounce ideas off of. They were also enlisted as assistant sleuths at the victim’s funeral.

- I created a teenage sidekick for Hannah who gave her access to a key site at the high school to search for proof that a teacher had committed the murder.

- I created a janitor who served as a trusted source of information—a see-all, know-all adult at the school to bounce ideas off of.

- Lastly, I relied on Hannah’s self-reliant personality and moral compass to dictate how she conducted her investigation. As such, I created a “rope-a-dope mechanism Hannah employed to interview suspects without them realizing what she was doing until it was too late and they had answered her questions already.

The Case of the Croaked Coach

Despite how guilty Dean looks, Hannah is convinced he’s innocent. When Snyder is arrested for Bixby’s murder, the wisecracking, irreverent amateur sleuth jumps into action to flesh out the real killer. But the trail has more twists and turns than a slinky, and nothing turns out how Hannah thinks it will as she tangles with a clever killer hellbent on revenge.

UNIVERSAL BOOK LINK: https://books2read.com/u/m20yWk

Named Best US Author of the Year by N. N. Lights Book Heaven, multi-award-winning cozy mystery author Susie Black was born in the Big Apple but now calls sunny Southern California home. She has published eight books as of May 2025.

She reads, writes, and speaks Spanish, albeit with an accent that sounds like Mildred from Michigan went on a Mexican vacation and is trying to fit in with the locals. Since life without pizza and ice cream as her core food groups wouldn’t be worth living, she’s a dedicated walker to keep her girlish figure. A voracious reader, she’s also an avid stamp collector. Susie lives with a highly intelligent man and is the mother of one incredibly brainy but smart-aleck adult son who inexplicably blames his sarcasm on an inherited genetic defect.

Looking for more? Contact Susie at:

Website: www.authorsusieblack.com

E-mail: mysteries_@authorsusieblack.com

Blue Sky: @hollysusiewrites.bsky.social

Facebook: Susie Black, author of The Holly Swimsuit Mystery Series | Facebook

Facebook: https://facebook.com/TheHollySwimsuitMysterySeries

Instagram: Susie Black (@hollyswimsuit) • Instagram photos and videos

LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/authorsusieblack-61941011

Pinterest: https://www.pinterest.com/hollysusie1/

You must be logged in to post a comment.