I was jolted by the comments of one of my beta readers for my newest Wanee Mystery, “Of Waterworks and Sin,” who was adamant that no one remembers anything before they connect images with speech, around 3-4 years old. There is even a name for it: infantile amnesia. Well, one reason I was taken aback was that the book is a historical mystery and I’m pretty sure no one knew of infantile amnesia in 1877. They might have wondered why some toddlers remembered incidences and others didn’t, but there was no advanced research or name for it.

As Doc in Wanee would say, “The memories are fragmented and horrible to conjure, and often, he seemed unsure of them. But the trauma may well have cemented them into his being.”

Babies, especially toddlers, do have implicit memories, they may remember being rocked, a sound repeated each day at nap time, or a certain food. But, as with all things, individual differences, cultural factors, and even the type of experiences a child has can influence how well and what they remember. In short, not all children have infantile amnesia, just the majority.

Here’s the challenge. As writers, we are enjoined to write about what we know. And what we know can be challenged by readers with other experiences that counter ours. One of our greatest instruments in showing and not telling are our memories: the smell of damp milk cows on a dewy spring morning, the sound of chickens clucking softly under the front porch as the milk truck rattles up the lane to pick up the milk cans for processing. Kittens mewling in a haystack. The smell of diesel fuel lying heavy over shimmering tarmac on a hot summer day. The roar of a jet, the rustle of leaves in a cottonwood. The smell of timothy grass after the rain. The sight of hands reaching down to you. The sound of footsteps approaching you from the rear as you walk between street lights. Sights and sounds and feelings all rolled into one big, massive evocative heap.

And so back to childhood memory. I remember being in a crib on a summer day in the apartment we moved from when I was 18 months old. I’m happily slurping on my bottle when my older sister holds her shiny silver cap gun at me, steals my bottle, takes a glug, and hands it back to me. Because my crib is against a wall that has two doors into the same hallway, she circles around and holds me up repeatedly until my bottle is empty. Witnesses assured me that the incident occurred before I was one year old. I remember that same sister running away from the same apartment on her tricycle with her pajamas stuffed in my mother’s vanity case. All of which, being my experience, informs the memory of the toddler in my story.

Yet my beta reader throws “modern science” into the mix, what the child remembers can’t be. But it can, and I know it. If I can remember these mundane incidents as clearly as I do, then why wouldn’t a traumatized 14-month-old have ingrained memories? Sights, sounds, pain, hunger, fear, and a kind voice.

“Ah,” Doc raised his eyebrows, which, from his expression, hurt. “He doesn’t remember so much as feel what he related. His mother put him down to sleep. Strange noises woke him. He couldn’t say what they were, only that he awakened. His stomach aching, he cried. A man spoke to him, and he believes gave him something to sustain him as the pain faded.”

I’m sure others have memories stretching back into infancy that disprove a blanket statement that all children have infantile amnesia. Especially when trauma is a factor. The question is, do you redo your story because of one beta reader especially in view of very positive results from the others? Or do you make a few adjustments assuming that one reader represents others but otherwise stand by what you know to be true?

You can find out.

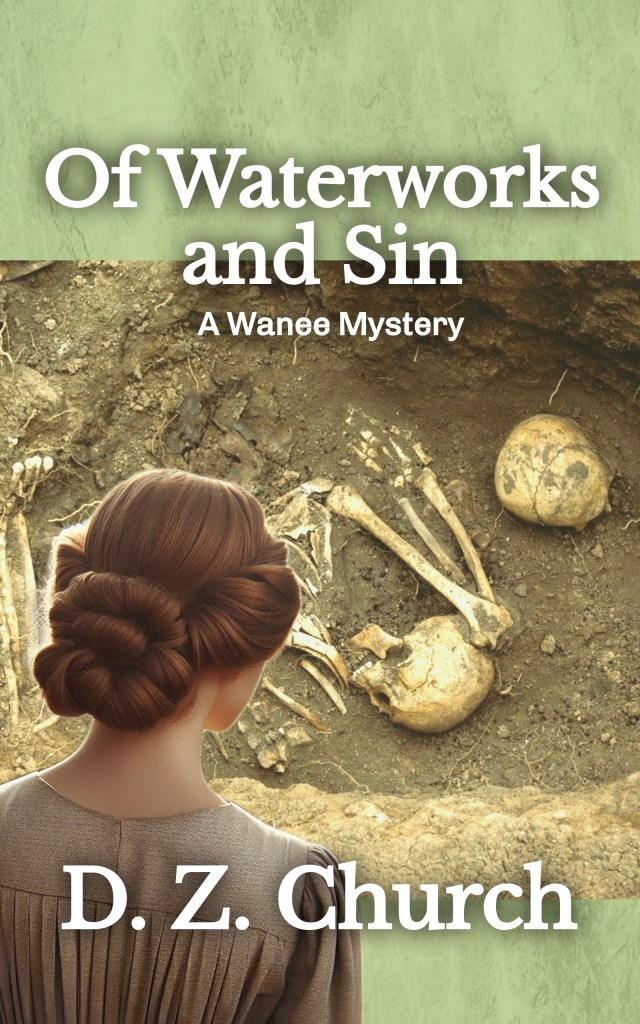

“Of Waterworks and Sin” will be published on April 15, it is available for pre-order now (https://www.amazon.com/Waterworks-Sin-Wanee-Mystery-Mysteries-ebook/dp/B0F151Z25Q/). Cora Countryman makes a promise to the owner/editor of The Courier that she intends to keep. Ignoring her dress shop and boarding house, she concentrates on publishing the daily paper. But when two skeletons are found in a trench meant for the new water main, she can’t resist investigating.

Discover all my books at: https://dzchurch.com

I just wanted to say that I have very strong memories of my early years in 1950s South Dakota, and none of them were traumatic. I don’t think you should change your whole story because of one reader’s opinion. Maybe it’s unusual, my sibs don’t have those kinds of memories, but many people do, so it’s my opinion that you’re good. Looking forward to reading your book.

Kestrel Geiger

LikeLike

Great post. I definitely remember something that happened when I was two years old. Quite vividly and can still picture it.

LikeLike

This is a great post! First on the beta readers- I have one beta reader whose knowledge I admire and use, but her values are more black and white than mind so I keep that in mind when she gives me feedback on books.

As for the memories- my husband can remember things back when he was two. I, on the other hand, only have brief memories from after the age of 5. But I think that’s because I had encephalitis when I was 5 and as I told my children, I can only remember so much because part of my brain was burned up from fever when I was young. LOL

And I agree with your thinking about the book being historical and how you handled it. Well done!

LikeLike

You’re spot-on with this one. I recently came across a short piece on advances in neuroscience that concluded that infants have memories but no way to access them, and hence can’t recall them in contemporary language. You story illustrates something I have long thought was obvious but overlooked–writers and other artists anticipate discoveries; we’re tuned into change and growth. Sci-fi novels are obvious in their depictions of the future, but all fiction writers’ minds are drawing together and exploring advances not yet fully articulated or understood. Great post. Thanks for giving me a chance to rant about one of my favorite things.

LikeLike