Most fiction authors are familiar with the debate about whether to use real locations, people, and real historical events in our stories; or whether to keep everything fictional.

There’s an argument to be made for both sides. Many book lovers enjoy reading about real places, and some even make the effort to visit a place because they’ve read about it. They might buy specific products mentioned in a book, or eat a particular meal that was described. I get it. I have sought out places and experiences that I’ve read about in my favorite stories.

Maybe I’m uniquely cursed, but the changeable nature of reality often comes back to bite me when I use something specific and real in my stories. It’s one thing when a story is clearly historical fiction, set far back in time, but when it takes place only a decade or only a few years ago, do readers actually keep track of when changes happened, or do they simply think the author is clueless?

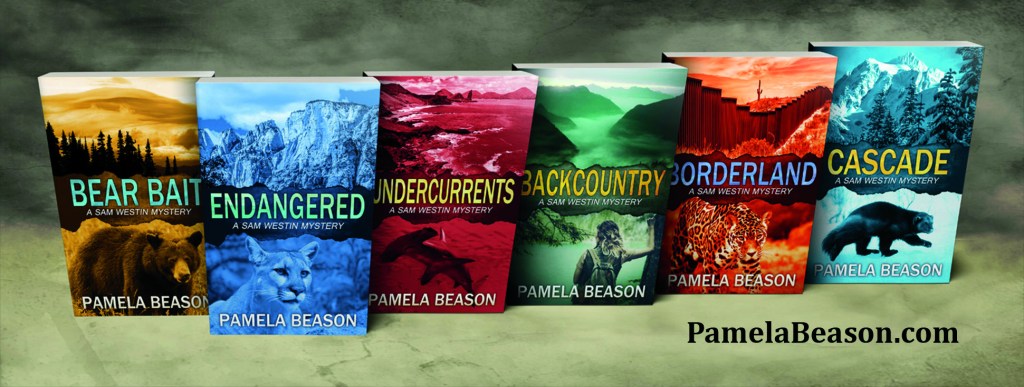

I started my Sam Westin series with Endangered, a story about the search for a missing child in a fictional national monument. My protagonist was submitting daily blog reports from the backcountry via satellite phone and computer connections. Needless to say, the technology that she was using more than ten years ago has changed drastically over the years. Do readers now think that I know nothing about technology? I’m afraid to take a survey.

When I wrote my mystery Backcountry, I decided to set a pivotal scene in a country western dance bar owned by an acquaintance of mine. I wanted more people to know about the place. Then, less than a year after Backcountry was published, the bar went out of business.

In Cascade, a mystery I published only a couple of years ago, I (or rather, my protagonist Sam Westin) made a big deal about how wolverines should be on the Endangered Species List in the United States, but they weren’t. Just a couple of week ago, I read wolverines had recently been added. Yay for wolverines! They deserve to be listed. But now, I’ve got to wonder: how many readers will check the publication date of Cascade and compare that with the date that wolverines became protected; and how many will simply conclude that the author of the book didn’t know what she was writing about?

To make matters more complicated, my state, Washington, is on a campaign to change the names of our popular waterways and parks because the person for which the place was named was white and basically, a terrible person to non-Caucasian people. For example, our Harney Channel, a major passage in the San Juan Islands here, was originally named for a 19th century U.S. Army general famed for abusive and even deadly actions toward Black and Indigenous people. Now it’s Cayou Channel, re-named to honor a Coast Salish Native American who was an upstanding leader in all ways for his time. Again, this is something to celebrate, but now even new maps seem to indicate that I don’t have a clue about local geography.

No doubt our state’s Committee on Geographic Names will change up a lot of things around here. After all, practically all the place names I’m surrounded by are called by the last names of white British officers who were on George Vancouver’s explorations, or named for white guys who were bigwigs in the Hudson Bay Company. And how long will it be before the Committee gets around to reconsidering our state’s name? George Washington was another old white guy and a slaveowner, after all.

The faster that technology and names change, and the faster that events change public opinion and even the course of history, the harder it is to write a good story that mentions real places and things. We authors are capturing snapshots in time, and that time seems to be getting shorter and shorter.

Maybe I’ll switch to writing science fiction and make up everything from now on.

I’m just wondering why this good blog post is no longer available. I wanted to comment, but my browser says it is not there. Huh.Jackie Houchin.

LikeLike