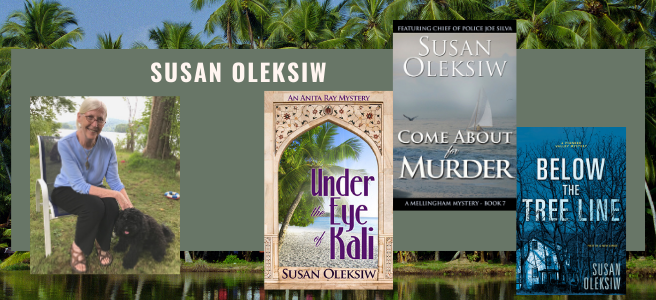

I’m in the middle of the sixth book in the Anita Ray series, which is set in a tourist hotel in a South Indian resort. Over the years the area has grown from a tiny fishing village with a few hotels just up the coast to one of the most popular destinations for Westerners eager for the sun and sand, not to mention the sunsets and the fishing boats bobbing on the horizon at night. I know the area well, having visited it for the first time in 1976 and several times in the 2000s.

The pathways laid out in the early years are now paved walkways through marsh with little pools covered with lily pads. The paths have been widened in some areas to allow shop owners to hang out rows of brightly colored silk saris and blouses. When I think there’s no more room for another restaurant or shop, I turn a corner and spot five square feet turned into an open-air cafe with the owner stirring a pot on a two-burner cooktop, ready to serve the foreigners sitting on stools before a board table. The food is good, the price is right, and the cook’s son works in one of the high-end hotels. Much of Kovalam has spread on what was once paddy fields that came down to a low berm fronting the beach. All those are gone, and only the rare private home remains, hidden away beneath tall palms.

A reader often tells me they know “exactly where I am” in an Anita Ray story, and that’s because I do too. I have a strong sense of direction in India (and elsewhere), a deep understanding of India (after years of graduate school), and a personal love of the region. All of that informs the Anita Ray stories. What I don’t have is a sense of place in any story if I haven’t been there, walked through a public park, found a typical cafe for the area, and visited a municipal building—perhaps a library or town hall. I can make up a lot of it, but I need to experience the “feel” of the place.

The Joe Silva series, in seven books, takes place in a small coastal New England town. I know these towns well, having grown up in one. The rocky coast speaks of the “flinty” Yankee, and the harsh winds call to mind the ever-present threat of hurricanes and other storms. Winters may be changing because of climate disruptions, but the birds still come, the land demands careful attention, and life for the fisherman is never easy.

One of the reasons I enjoy reading crime fiction is the other landscapes I get to explore. I’ve been through the Southwest and lived for a brief time in Tucson, so I appreciate any writer who can take me into that world of mountains and deserts, long straight roads, and small adobe houses with gravel yards. The openness of Montana and Wyoming brings out the best in some writers, and I look forward to their stories and landscapes.

Regardless of where we grew up or now live, we are creatures of our environment, and the best fiction uses that sense of place, what is distinctive and unique about one location, to propel the characters and their story. This, for me, is the reward of a reading a novel with a rich, fully developed setting. I come to understand both people and place, and know a part of the world I may never visit a little better.

You must be logged in to post a comment.