In the summer I’m usually deep into editing an anthology, and this year is no different. I’ve been doing this for most summers since 1989, when a friend and I started The Larcom Review. This summer I’m working on the third anthology from Crime Spell Books, which I co-founded with Leslie Wheeler and Ang Pompano, and have continued with Leslie and Christine Bagley. Our third anthology is Wolfsbane, which comes after Bloodroot and Deadly Nightshade,. in the annual series of Best New England Crime Stories.

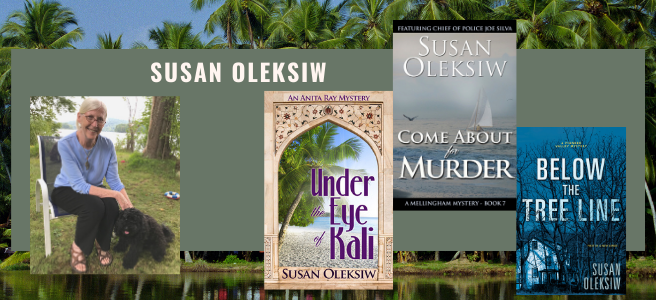

This wasn’t going to be my topic for today but I find myself thinking about the sixth Anita Ray mystery I’m working on somewhat desultorily. And this is a surprise because when I sit down to write my thousand words for the day, sometimes after having skipped a few days, the characters keep surprising me. The setting in a resort in South India is the same but nothing else is quite so.

One of my walk-ons got himself killed, though I don’t know why or exactly how; I just know he’s very dead, at the bottom of a cliff in the Kovalam resort. I’ll have to figure that one out. And the expected main character has morphed so many times that he may morph himself right out of the plot, even though that’s not my intent. Meanwhile the counter to Anita Ray has turned out to be more fatuous than anticipated but has thrown one of the best spanners into the plot. And I finally figured out why an elderly woman was able to leave India, without a husband to support her, and move to the States with her young son. None of this is in the synopsis I roughed out several weeks ago, and none of it tickled my brain while I was writing it. It seems to have been hidden in my fingers or the keyboard.

But the most amazing discovery is Anita Ray’s perspective on her own work as a photographer. She has been adopted as a mentor by a young man who is clearly gifted and comes to her for advice. She’s willing to help and enthusiastic about his work, recognizing his distinctive use of color, texture, pattern. He has some gaps in his technical knowledge, and limitations financially; he can’t afford to have every image printed out for examination and critiquing. But he obviously has a bright, perhaps significant future if he can hold on under difficult circumstances. His work and trust in her judgment set Anita thinking, and she enters a phase of an artist’s career that can be deadly or transformative.

I have no idea what will happen to him. He could be a figure in the mystery itself, dropping clues or finding them, or another victim, or just someone who brings Anita to the fore in a different way, which would make him useful but little more than a background figure. I don’t know now and won’t know until I write again and pose the question.

All this began when I came across a post by Michele Dorsey challenging writers to write one thousand words a day without any plot outline or specific goals. A thousand words is far less than my usual daily goal when I’m working on a novel, so I thought I could fit that in easily while I was working on the anthology. And I did, for a while. Now I write three days in a row, for example, and two days doing something else. And there’s no reason for this except myself-discipling seems to be flagging.

Peter Dickinson, one of my favorite writers, was once asked if his characters took on a life of their own, a fairly standard question for a writer. He replied that there’s little room for surprises in his work once he starts writing because he develops an extremely detailed outline before he begins. I tried that once, and it didn’t work for me, so I admire anyone who can do that. Until that talent comes to me, I’ll continue discovering the world of my characters, and hope it all makes sense. It will be weeks before I know, so I’m learning patience—again.

You must be logged in to post a comment.