I don’t ever think of myself as having writer’s block but I know that when I’m not sure about what comes next in the novel I’m working on, I tend to turn to photography and play with the camera and old photographs. Aside from my love of photography in general, I find this other art form stimulating in a way different from writing.

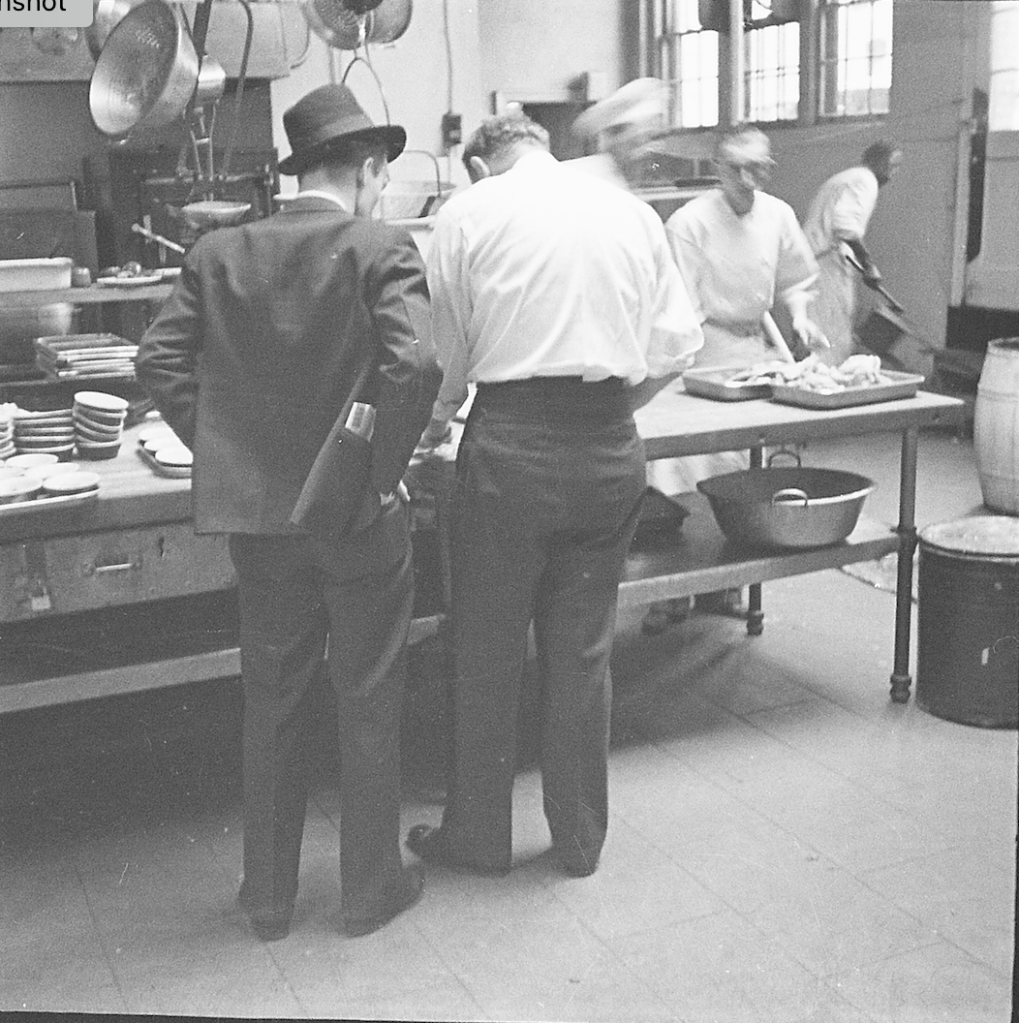

lately I’ve been going through old photographs, some dating to the 1930s taken by various relatives and a few dating to just the early 1900s when my grandparents were courting. My grandfather photographed as a sideline and occasionally sold photographs to Look and Life when they were new. Granddad preferred the modern world—photographing machinery, industrial sites, and 1950s gas stations and fast-food joints lining a highway. My mother preferred landscapes. I like people and color. Granddad was a milk inspector for much of is career.

My family traveled around the United States in the 1940s, 1950s, 1960s, so I have photographs of us visiting various national parks, camping, riding, hiking, and, rarely, looking into shop windows. One summer we rented an RV and traveled up and down the Pacific coast, pulling up next to an RV from California or another western state. My dad often commented, “Too bad we don’t have a license plate from home.” He meant Massachusetts. Any time a park service officer found out where we were from, we were treated like celebrities. This was in 1959, when you could arrive at the Grand Canyon at five o’clock in the afternoon and find a good camping spot still available.

Most of the photos from this trip are of magnificent canyons, mountains, lakes, and other scenery. We never had trouble getting a good view; there were few crowds and no cell phones—no one taking selfies but lots of people taking pictures of each other on the top of a mountain or paddling a canoe.

It’s an odd habit but photographers often take several pictures of the same person in different positions and poses at the same event, and save all of them, not just the best one. Sometimes the photographer takes three or four of almost identical images. In one instance I came across so many of the same person that it looked like individual cells from an old movie.

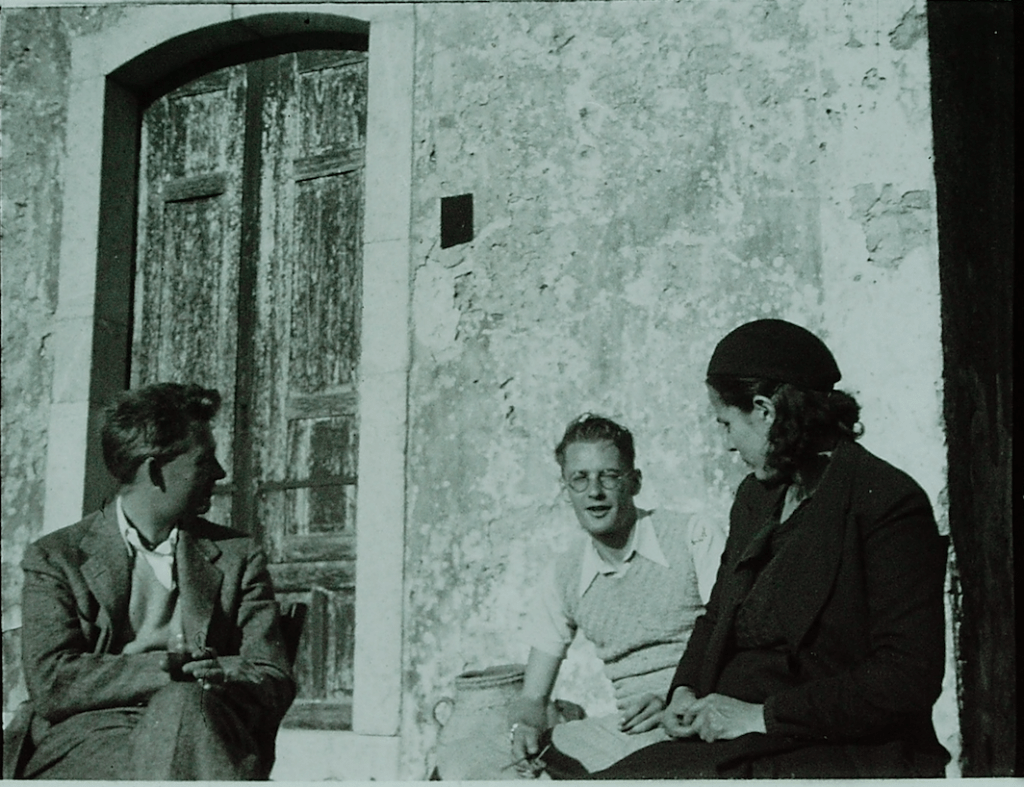

The images from the 1930s and 1940s are of people I didn’t know or know only through family lore, so I’m free to imagine their stories. I rearrange the images in different sequences, much like rearranging scenes in a mystery novel, and a variety of scenarios come up. I especially like the ones of my father chatting with new friends in Sicily in 1936, when my parents took an extended honeymoon to Italy and Greece. That’s Dad on the left.

After a few hours of this ideas for my current project start to bubble up and I quickly turn to taking notes. This afternoon, after feeling stalled about the ending though I was writing scenes that had to be written, I had a slew of ideas coming. I made lists of actions my characters had to take to get to the climax, each a scene by itself leading to the final confrontation. My attention is back on the novel, and I’m putting away the photography for another day. But it will be back.

You must be logged in to post a comment.