Here’s a quote from Ian Fleming, World War II Naval intelligence officer—and author of the James Bond novels:

Never say ‘no’ to adventures — always say ‘yes.’ Otherwise, you’ll lead a very dull life.

Dull life? Not me.

Recently my life has been anything but dull. Though not the way I planned it.

When I wrote the first draft of this blog, I anticipated it would appear days after my return from two glorious weeks in Bella Italia.

Naples, Pompeii, Herculaneum. Rome, the Eternal City. The Vatican museums. The Coliseum. Florence, steeped in art, the statue of David looming over all of it. Venice with its canals and gondolas.

It didn’t happen. I had to cancel the journey I’d been planning for over a year.

A week before I was due to leave, I started getting low heart rate alerts on my Fitbit. Off to the emergency room, where an afternoon of EKGs, bloodwork and doctor consultations revealed that I needed a pacemaker. The doctors didn’t advise traveling for four to six weeks. Surgery, then home, then back to the ER with a fluctuating heart rate—again. One of the leads on the pacemaker had come loose. Another surgery, this time to replace that lead and reposition the others. I came home from this second hospital stay the day I was supposed to leave for Italy.

The travel insurance claim is in the works, and I’ve rebooked the trip for next spring. I’ll get to Italy yet.

So, why Italy? It’s the same reason that led me to Greece two years ago, and an upcoming trip to Egypt in January. History and art. I have an MA in history and all those books on my shelves. I love going to museums and wandering through galleries full of wonderful art. My favorites, the Impressionists. When I was in Paris decades ago, I went to the Louvre three times and the Orsay Museum twice. I sought Monet at the Orangerie, the Marmetton and took a trip to Giverny, where he painted and where I discovered he loved Japanese woodblocks as much as I do.

I used to say I didn’t like modern art. Then some years ago, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art mounted an exhibit featuring Richard Diebenkorn. I went twice. Time to take a different look at modern art and understand it a bit more.

I took an art history course. I’d always thought about doing that when I was in college and never got around to it. I enrolled at the local community college and went to classes, accompanied by the weighty tome I bought in the college bookstore. I was the oldest person in the room, including the instructor. I learned a lot.

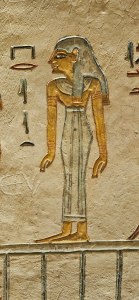

The class broadened my appreciation of art and reignited my desire to travel. Not to the land of the Impressionists, but to the ancient world. Hence the trip to Greece. I climbed to the top of the Acropolis and marveled at the treasures in the Archeological Museums of Athens and Crete. I saw the statue of the Charioteer in Delphi. On Santorini, I went to the ruins of Akrotiri, a town destroyed by a volcanic eruption in the 16th century BCE.

I could happily go back to Greece, as there is much to see and I barely scratched the surface. Italy has been rescheduled for next spring. Now I’m anticipating Egypt. Cairo and the Grand Egyptian Museum. The pyramids and the Sphinx. Abu Simbel, Luxor, the Valley of Kings. Sailing the Nile on a boat and envisioning Amelia Peabody! I can’t wait!

Later in the year, I’m planning a return to England and France. In keeping with my interest in history, especially World War II history, I’ve signed up for an Operation Overlord tour that starts in London, with the planning of the D-Day invasion, and includes visits to Churchill’s War Rooms and the Imperial War Museum. Then to Bletchley Park, where Allied codebreakers cracked the Axis codes. From there to Portsmouth and a cross-channel ferry to Normandy and the D-Day beaches.

Of course, if I’m going to England and France, I’m spending extra days in both places. Versailles, a tour of the Paris Opera, perhaps another trip to Giverny. As for England, I’m checking to see what plays and musicals are playing in London’s West End. The Museum of London, one of my favorites. The British Museum, a must. Afternoon tea at Brown’s Hotel, of course. That’s where Agatha Christie always stayed. And it’s the scene of her Miss Marple novel, At Bertram’s Hotel.

After that? Where shall I go next? Vienna? Australia? Costa Rica? Iceland? Spain? My wish list gets longer and longer!

And yes, there’s an art history plot in here somewhere. Remember, in my latest Jill McLeod/California Zephyr book, Death Above the Line, a Vermeer looted by the Nazis appears—then disappears. What happened to it? Eventually I’ll have to find out.

You must be logged in to post a comment.